I’m in Palo Alto, CA for four days attending the Stanford Medicine X (#MedX) conference, which focuses on emerging health-care technology and patient-centered medicine. The first day was a pre-conference workshop on Partnering for Health in clinical trials.

I’m having a blast! It’s like a giant TweetUp of patient advocates, healthcare providers, and technology innovators. I’ve met a dozen people that I’d previously only known online. Several of them are patients who are healthcare bloggers and tweetchat moderators like me and have diseases different than mine (diabetes, arthritis, lupus, other cancers, etc.) My roommate is a delightful young pre-med student who happens to love chocolate, and who has had no sense of smell for as long as she can remember (which is fortuitous, considering one of my Xalkori side effects).

Presentations and panels address the evolving nature of healthcare, with a strong emphasis on patient involvement. Some topics:

–How to include the patient voice when designing clinical trials

–How do patients who are not tech savvy (“no smartphone patients”) obtain medical records and learn about their disease?

–Technology to assist those with disabilities

–New apps and devices for improving outcomes (e.g., a device that tracks when bedridden patients need to be turned to avoid bedsores)

–The value of relationships in promoting health

–Training medical students and doctors to incorporate empathy in patient care and ask the patient what is important to them

–Patients self-tracking their health data (e.g., diabetes blood levels and insulin doses)

–Which metrics to use when choosing a doctor, and where to find them, and new ways to gather the info

At least half the people in the audience are interacting with their smartphones, laptops and tablets during the event. I can see how all the online activity is extending the reach of the conference, which is also being streamed live (except when the server crashes from overwhelming demand). It is fascinating to watch the presentations and simultaneously read a very active #MedX Twitter stream that summarizes, critiques and expands on what is being said.

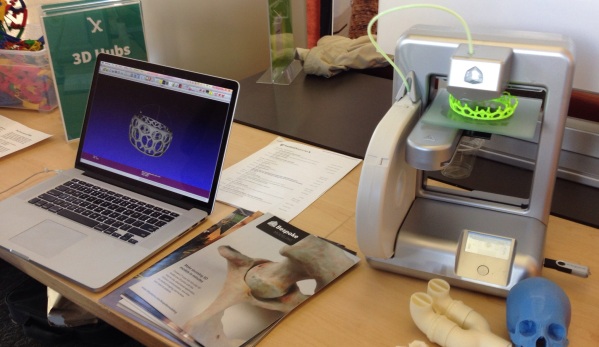

I’ve seen some cool vendor demos also, like 3D printing of medical models and devices:

My speech is tomorrow (Sunday September 7) at 10:10 AM PDT. Hope you’ll be watching via Medicine X Global Access! If you miss it, it will be posted online eventually.

I fly to Denver Sunday evening for my eight-week scan on Monday. I must admit this conference is a great scanxiety distraction.

See? I DID make it to second base! (Credit: Sandi Allen Estep)

See? I DID make it to second base! (Credit: Sandi Allen Estep)