45 years ago today, Mount St. Helens erupted. From my home in Tacoma over 70 miles away, I could hear and feel the blast and see the plume of ash, rock, and hot gases rising into the atmosphere.

Such major blasts of chaotic energy and hot gases produce extensive damage. The explosion darked the skies for miles, extinguished lives, erased forests, and rearranged the landscape. The melted glacial ice generated a lahar that carried away homes, destroyed highway bridges, and clogged shipping lanes. The blast left behind tons upon tons of pulverized rock that continue to cause challenges for communities living downstream–such as clogging their drinking water systems.

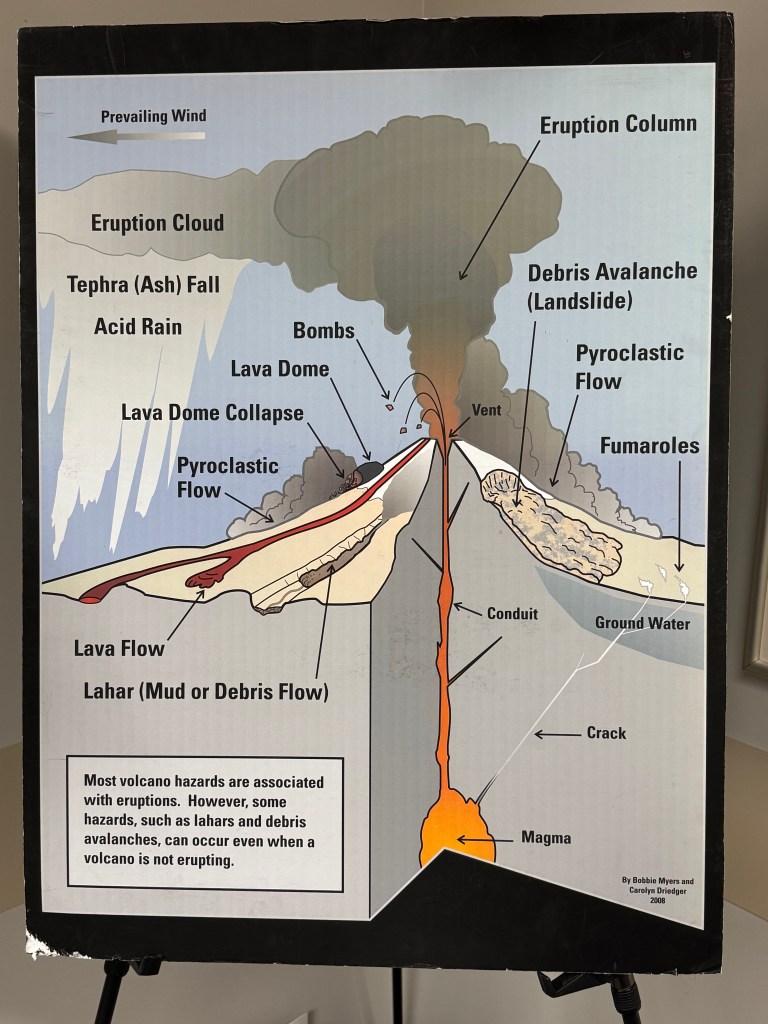

Mount St. Helens is now one of the most closely monitored volcanos in the world. Last Saturday at the Cascade Volcano Observatory (CVO) open house I learned about different types of volcanoes, effects of eruptions on living creatures and the earth, how we track and model earthquakes to predict eruptions, understanding lahar flows so we can provide early warnings, and atmospheric influences on that guide ash and volcanic gas distribution. Models for making these predictions depend on data gathered by a variety of sources, such as weather balloons launched by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). We can’t prevent volcanoes from erupting, but we can improve our preparedness and detection abilities so we can help reduce deaths and damage–IF we can learn from history and maintain the will to and funding to do what is necessary.

The posters I’m sharing in this blog were on display at the CVO open house. CVO is part of the Volcano Hazards Program run the by U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), which is under the U.S. Department of the Interior. Many USGS scientists and staff have departed in response to government actions of the past few months. In May the federal government has notified USGS researchers and students that their funds could be frozen and staff could be laid off. Other government cutbacks (such as reduced weather balloon launches) reduce USGS ability to monitor volcano activity, not to mention the U.S. Weather Service’s ability to predict tornadoes and other severe weather.

Despite the devastation, signs of life returned to the desolate blast zone within months, but it will never appear as it did before the eruption. If we don’t actively pursue the objective study of our world, we not only limit our learning about the world we live in, we will become less able to predict impending disasters and protect lives. Guess we’ll just have to adapt when natural disasters strike. If we can.